Over two days in September, a group of elected officials, traffic engineers, and bike advocates from Santa Cruz County gathered with Dutch transportation planning experts to consider large and small ways to improve bicycling in our community. The workshop was sponsored by Gazelle Bikes and Ecology Action and led by the Dutch Cycling Embassy, a network of public and private partners who work together to create bike-friendly cities. Over the course of the two-day workshop, attendees took a deep dive into Dutch biking infrastructure design and brainstormed ways to incorporate what they learned into Santa Cruz County. Now, the workshop report is ready to summarize key lessons, and we encourage you to dig in and get inspired.

The report focuses on the Dutch approach to roadway design, which they call “hardware.” The first step in the design process is network planning, which aims to identify a network that works well for people in cars as well as people on bikes. The planners emphasized the balance between “place,” or the quality of a street that makes people want to linger (think Pacific Avenue), and “flow,” or the need to move people efficiently through an area (think Soquel Drive). An important initial step in network planning is to decide where to prioritize place and where to prioritize flow and then design streets accordingly.

A major theme of Dutch planning is designing for safety, which includes designing for lower speeds. There is a wealth of data that shows that higher speeds increase the likelihood of death or severe injury when a collision occurs. The presenters shared Dutch street classifications, which identify street types with the target speed limit and type of bicycle facility. Arterial roadways in the Netherlands commonly have one car lane in each direction, a speed limit of 30 mph, and separated cycle tracks. For comparison, arterial streets in the United States commonly have two car lanes in each direction, a speed limit of 40 mph, and Class II painted bike lanes; this is not a comfortable environment for people on bikes. Neighborhood streets in the Netherlands have speed limits of 20 mph and do not have separate bike facilities. These streets are shared by bikers and drivers, but the design is safer because of lower traffic speeds and increased social interaction and negotiation among road users.

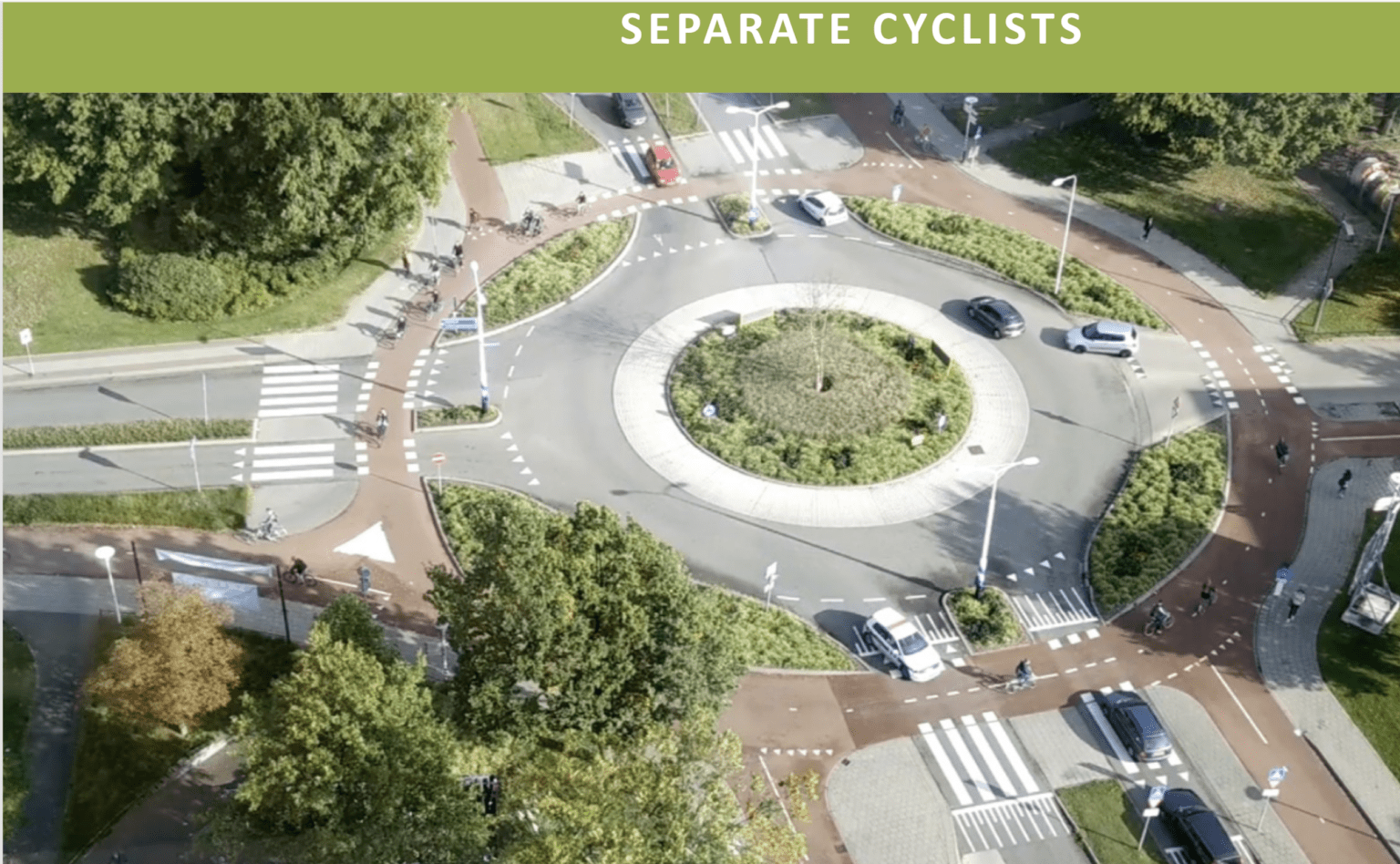

The idea of reducing vehicle speeds and the number of lanes on arterial streets raised some eyebrows among workshop attendees, but according to the Dutch planners, this design still allows motor vehicle traffic to flow smoothly because of their secret weapon: roundabouts. On an arterial roadway in the Netherlands that prioritizes flow, the number of intersections is reduced, and traffic lights are replaced with roundabouts. This means that drivers do not have to stop at each intersection, just slow down while moving through each roundabout. Drivers travel at slower speeds, but travel times are similar because drivers are not stopping and waiting at each traffic light. This design not only frees up space for separated bikeways but also, according to the Dutch planners, improves conditions and reduces stress for drivers. Imagine not having to worry about missing a green light or waiting for what feels like forever for a pedestrian to cross a gigantic intersection!

Roundabouts have important safety benefits, too. While a typical signalized intersection has thirty-two possible points of conflict among pedestrians, bikers, and drivers, roundabouts have only eight. The Dutch planners were adamant that there are right and wrong ways to design a roundabout. Dutch roundabouts include separated bike lanes outside the motor vehicle lane, and the planners recommended one lane of car traffic only. They called the two-lane roundabout an “advanced-level” design that American drivers are not ready for.

The report concludes with a list of recommendations for Santa Cruz County as we are thinking about how to improve our streets and roads. Recommendations include applying comprehensive network planning to all jurisdictions, prioritizing completion of the main cycling routes across the county, and planning for more roundabouts and protected intersection treatments. There were also recommendations for smaller-scale changes—like upgrading bike parking across the county and using green asphalt to make the entire bike lane green, which alerts drivers to expect people on bikes and is potentially less expensive than the thermoplastic treatment that is currently used for green lanes.

At the end of the workshop, attendees were left energized and inspired by the possibilities for Santa Cruz County. See how that pivotal experience is resulting in tangible progress: Complete Street Initiative.